As my month ends I’ll try to wrap this all up – calendars as signifiers of epistemological differences, crossbloodedness, water stories, and bizarre questions like: are Newton’s laws natural? – in a lumpy bumpy bundle.

And thank you all for the great honor of doing this in visibility to your presence. OK.

I drive three hours through clouds and mild snow and park in a residential neighborhood of detached houses with garages and yards in the Bronx. A thin white veil over the intricately landscaped entrance sparks rainbows as the sun comes out. Two Padrinos lives upstairs and a bembe, a drumming ceremony, is taking place in their immaculately white cellar that has been fitted for Orisha work: initiation, drumming, divination, other ceremonies.

As I walk down the stairs to enter my ile – my home – my glasses mist over with steam succulent with spice from a feast being prepared in the kitchen, mingled with body heat in the already full room. I shed my coat and hang it in the closet. Some people, as I am, are dressed all in white to honor Obatala; some choose to honor another Orisha, perhaps their own. People of all shapes and sizes are gracefully covered with mostly white and light or brightly colored cloth, more or less from neck to ankle. Many women wear long full skirts; some wear beautifully tied head-wraps; some men wear bandanas, or caps, or little Yoruba hats that look like rakish mushrooms; faces of all colors shine beneath. The faces of those who have been dancing are brighter yet with the sheen of delighted perspiration.

I step into the room, pass the ancestor altar, and look for my Madrina on my way to greet Oshun, the Orisha we’re feting today. People are greeting me, I them, at every step. I know some intimately and others barely at all; we share genuine joy in working the beloved Spirit together. The musicians are playing a liturgy in song and drum language – barago, ago, Yemoja, barago ago, oro mi – open the way for my mother’s tradition! Almost everyone present is singing and many are dancing matching steps in a series of fluid lines that meander across the tightly packed space. Those nearest the drums are elegun, possession priests.

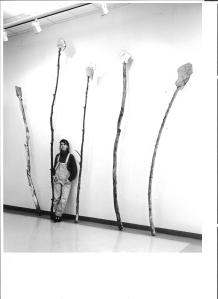

The musicians and most ‘children of the ile’ arrived before noon; others come and go throughout the day, some dressed in work clothes. When each arrives he or she salutes the trono, a sculptural installation in which the vessel of an Orisha is enthroned. The area is demarcated and draped with costly cloth. Because we’re paying homage to Oshun, owner of sweet water, and because her priest is exceptionally artistic in his devotion, there is an actual running waterfall bedewing a multi-layered forest in mist. Deep in this forest, a sculpture honoring Oshun gleams mirage-like, almost hidden by filmy draped cloth that undulates in air currents and signifies animate spirits. Paintings and sculptures of trees, peacock feathers and fans, complete the shifting palimpsest of veils around the throne. Flowers, fruits, and delectable dishes are aesthetically displayed in offering to Oshun herself. The clay vessel that contains medicine to amplify the deity’s awo, her secret, is elevated and gorgeously dressed.

A young policewoman arrives in uniform. Its dark cloth, her narrow trousers, the gun and stick and handcuffs secured to her belt, stand out in the crowd. She prostrates herself before the trono and Padrino lifts her. Although I can’t hear her voice over the drumming and singing I see that when she rises she’s crying; she dries her eyes to go back outside, back to the work of policing the secular world. On her way she touches the floor to salute Baba Angel, who dances before the drummers. As she ascends the stairs people start to call out “Omi, Yemoja!” Baba Angel has begun to show signs of possession by his Orisha, Yemoja, the great mother, mother of fishes, mother of the world. All Oshun’s sweet water flows to Yemoja’s sea and her visit is a culmination; the policewoman leaves with a serene smile on her face.

I can just barely see Baba Angel’s luminous dark head, the light-dark dark-light patterning of the sea-like motions of his slender dark arms and white sleeves as he spins amongst the rhythmically shifting waves of dancers who call Yemoja’s name. He is moving towards the trono where he disappears to the floor and rises hidden by several priests, is accompanied inside a small white-curtained enclosure.

The next time I see him he is the mother, he is she, is Yemoja, and around her waist she wears a blue and white flowing wrap. She moves royally through the crowd, followed by an attendant who carries jicara gourds of fresh cool water, of molasses. When I salute her she lifts me, rocks me in her arms, then pours some of her molasses into each of my palms and tells me to eat. She says she will give me everything I need to fulfill my destiny. An observer comments that Baba Angel “has a very sweet Yemoja” and as she gracefully dances away I agree.

That the possessed body is male is irrelevant to us as we salute our mother Yemoja, but an outsider observes a man speaking in a light voice, wearing something reminiscent of a formal skirt and dancing the swaying ‘feminine’ dance of the ocean in peaceful mode. If the Santero happens to be a gay man – and in our ile he is as likely to be as not – the outsider may also infer a gender performative dimension to possession. It as at this point in our “unspinning the cocoon of Western stereotypes” (Wangari Matthei) that we encounter the tangled heritage of nineteenth century race and sexuality theories, an Afrophobic heterosexist/sliding invert model knotted in place by racialized gender, gendered sex, and sexualized possession, promulgating the delusion that possession is ownership and ownership is control.

To ile members when Yemoja, the owner of salt waters, appears among us, she is herself, not a man performing Yemoja. The young man, the Santero, will not have any memory of the healing, gifts, and advice Yemoja bestowed on us through the medium of his body, and when she leaves he will dance with us again. When he leaves this life, she will arrive through others, riding them, as Zora Neale Hurston explains, like horses. Who will these horses be? Orisha don’t care if the horse they ride is rich or poor, black white red green purple or speckled, male female hetero homo asexual or all-sexual, short tall skinny or fat, a graceful dancer or a person who hobbles with a cane. What do any of these things have to do with character? They bear with us patiently as their devotees, a motley crew of 21st century Americans, slip slide or struggle beyond our varying cultural conditionings. Suuru baba iwa – patience is the father of character – and iwa pele, good or gentle character, an elision of the longer phrase i wa ope ile ( “I come to greet the earth”) is the cornerstone of Yoruba philosophy (Fatunmbi, 2005, 70).

People enter and leave the dance the room the world – we continually flow in and out of existence and Oshun and Yemoja, the owner of sweet water and the owner of salt water, continue to flow as our blood. The sweetness Oshun owns flows into the saltiness Yemoja owns, evaporates to become clouds owned by Obatala that are moved in the possession of Oya, the wind, to fall as rain and once again feed Oshun’s creeks. Their constant exchange makes it plain that possession does not denote the Western notion of control over, power over. Instead, olo, the word translated from Yoruba as “owner,” is literally spirt-brings-spirit, indicating someone or something having the quality of,beingrepository of, being responsible for or to. In Yoruba theology if anyone holds onto ownership, ibi commences. Literally ‘afterbirth,’ ibi refers to misfortune, understood as arising from resistance to change – what was nourishing, if held inside, leads to illness. Too much communal ibi, and life on Earth will cease. EuS schemata have inevitably led us towards just such a crisis.

So I’ve said it again, and I’ll say it again: translating epistemological difference has become a matter of life or death. These can be macro differences – such as the that between my mind on what’s right and the kind of thinking represented in treatment of Kelley Williams-Bolar – or same-differences, such as those I’ve brought tastes of from my Ojibwe and Orisha families to the table of this blog (told you upfront I was crossblood). Or micro differences, existing even between twins. I’ll end with another Yoruba saying: if your life gets better, my life gets better. Different as we may be, we have one thing in common: we’re all in this together.